Psychotic depression isn’t just severe sadness, it’s a brutal collision of mood and madness. Learn to recognize its hidden signs and why conventional antidepressants often fail. I still remember James, a brilliant engineering student who came to our clinic convinced his bones were dissolving. His blood tests were normal. His X-rays showed nothing. Yet he could *feel* his skeleton turning to dust. This wasn’t hypochondria, it was psychotic depression, a condition where severe depression partners with reality-distorting psychosis. What makes this illness so devastating is that sufferers often don’t report their hallucinations or delusions, fearing institutionalization or simply not realizing these visions aren’t real.

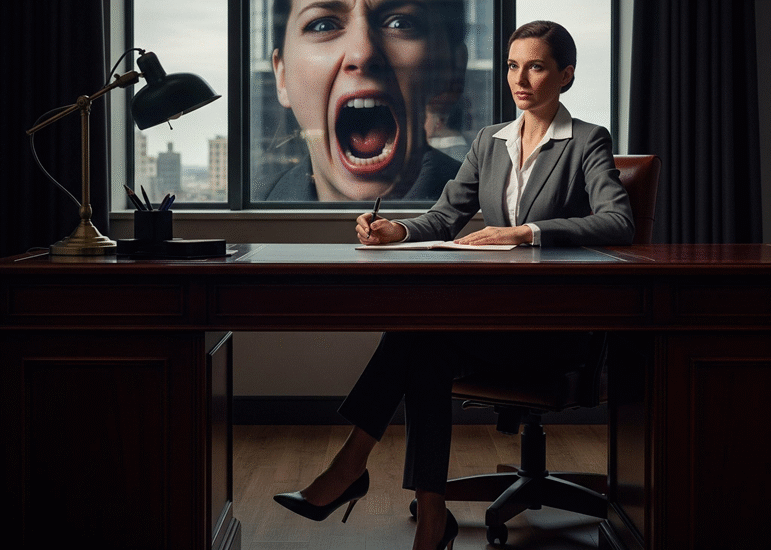

The Silent Scream of Psychotic Depression

Unlike typical depression where sufferers recognize their hopeless thoughts as symptoms, psychotic depression traps people in a nightmare they believe is reality. A mother becomes convinced she’s already dead and her children are imposters. A CEO secretly believes his colleagues are broadcasting his failures through office lights. The cruelest trick? These patients often appear high-functioning, their paranoia drives them to hide symptoms meticulously.

The hallucinations tend to be mood-congruent, voices whispering accusations, visions of rotting food symbolizing their self-worth. I’ve treated patients who smelled non-existent smoke from their “burning soul” or felt insects crawling under skin that was perfectly smooth. These aren’t metaphors to them, they’re irrefutable truths.

Why Antidepressants Alone Fail

Standard depression treatments often crash against psychotic depression’s walls. SSRIs might slightly lift the mood component while leaving the psychosis untouched like giving cough drops for pneumonia. The brain chemistry here is fundamentally different: excessive dopamine activity creating psychosis alongside depleted serotonin/norepinephrine causing depression.

The breakthrough usually comes with antipsychotics paired with antidepressants or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for severe cases. I witnessed a woman who hadn’t spoken in weeks, convinced her vocal cords had been removed greet her sister by name after her third ECT session. That said, medication is just the first prison break, the real work comes in psychotherapy helping patients distinguish illness from identity.

The Diagnostic Tightrope

Spotting psychotic depression requires Sherlock-level observation since patients often conceal symptoms. Telltale clues include:

Sudden preoccupation with religion or the occult in previously secular people Unexplained paranoia about being watched or controlled

Odd somatic complaints with bizarre explanations (“my kidneys are filled with lead”)

That eerie “smiling depression” where affect doesn’t match reported symptoms

I once missed the diagnosis in a teenager until her mother mentioned she’d been “talking to the stains on the wall.” The girl believed they were faces of children she’d supposedly harmed, a classic psychotic depression delusion masked as typical teen moodiness.

Treatment Beyond Pills

Medication stabilizes, but true recovery requires rebuilding shattered reality testing. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for psychosis (CBTp) helps patients develop “reality checks”, if the voice says you’re worthless, what’s the evidence for/against that? We create behavioral experiments: “If you’re truly being watched by the FBI as you believe, would posting this harmless social media update change anything?”

Family therapy is crucial too, loved ones learn to avoid either humoring delusions (“Yes, the TV is sending you messages”) or aggressive confrontation (“That’s crazy talk”). Instead, we teach empathetic non-agreement: “I don’t see the messages you do, but I believe they’re real to you.”

The Fragile Road Back

Recovery from psychotic depression isn’t linear. There’s often residual “insight”, patients may intellectually know their delusions were false but still *feel* their truth. One man who believed he’d caused 9/11 could later say “That wasn’t rational” while still fighting visceral guilt.

Relapse prevention becomes critical. We identify prodromal signs—when a patient starts noticing patterns in random events or hearing whispers in white noise, it’s time for a medication adjustment. Support groups help immensely, though many patients prefer those for general depression rather than schizophrenia-spectrum groups where they don’t fully identify.

Psychotic depression reminds us that the mind can be both the wounded and the weapon. But with proper treatment, even the most imprisoned psyche can find its way back to shared reality, one fragile, courageous step at a time.

References

National Health Service. (2023). *Psychotic depression*. https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/psychotic-depression/

Healthline. (2012, March 29). *Psychotic depression: What is it, symptoms, causes, and more*. https://www.healthline.com/health/depression/psychotic-depression

MedlinePlus. (2024, October 20). *Major depression with psychotic features*. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000933.htm

TalktoAngel. (2024, December 2). Psychotic depression: Symptoms, causes and treatment. https://www.talktoangel.com/blog/psychotic-depression-symptoms-causes-and-treatment

Cadabams. (2024, December 17). Psychotic depression: Symptoms, causes and treatment. https://www.cadabams.org/blog/psychotic-depression-complexity-and-management

Neurish Wellness. (2025, March 11). Psychotic depression: Symptoms, causes & treatment. https://neurishwellness.com/psychotic-depression/