I first met Michael when he was seventeen, working at a local grocery store where he bagged groceries with meticulous care. Intellectual disability involves unique strengths and challenges. Discover how to support individuals with intellectual disabilities in reaching their full potential through understanding, accommodation, and respect. As he carefully placed each item, he’d look customers in the eye and offer a genuine compliment about their choices. “These are good oranges,” he’d say with authority. What struck me wasn’t his Down syndrome, but his extraordinary ability to make people feel seen. His manager later told me Michael had transformed the store’s culture simply by being himself. That experience taught me what years of textbooks couldn’t: intellectual disability isn’t about limitations, it’s about different ways of being human that can enrich us all if we create space for them.

Intellectual disability represents a different cognitive wiring that affects learning, problem-solving, and adaptive functioning. The diagnosis typically involves three criteria: significant limitations in intellectual functioning, challenges in adaptive behavior across conceptual, social, and practical domains, and onset before age eighteen. But these clinical definitions barely scratch the surface of the human experience. I’ve known individuals who couldn’t read but could fix any small engine, others who struggled with math but possessed extraordinary emotional intelligence that made them natural peacemakers in their communities.

The spectrum of intellectual disability is remarkably diverse, ranging from mild to profound. A person with mild intellectual disability might live independently with some support, while someone with profound disabilities may need comprehensive assistance. What’s often misunderstood is that these categories describe the level of support needed, not the person’s worth or potential. I’ve watched individuals initially labeled “severe” blossom with the right accommodations, revealing capabilities no one knew they possessed because no one had previously created the right conditions for them to flourish.

The causes are as varied as the individuals themselves. Genetic conditions like Down syndrome and Fragile X, prenatal exposures to alcohol or toxins, birth complications, and childhood illnesses can all contribute. Yet in nearly half of the cases, the specific cause remains unknown. This mystery reminds us that intellectual disability is simply part of the human condition, appearing in families of all backgrounds, education levels, and economic circumstances.

Early intervention proves crucial but isn’t always a magic bullet. While therapies during childhood can dramatically improve outcomes, I’ve witnessed remarkable growth in adults who received proper support for the first time in their fifties or sixties. The human capacity for learning never completely disappears, though it may follow different timelines and pathways. One man I worked with learned to read basic words at fifty-two, not because he suddenly became capable, but because someone finally used the right approach and believed he could do it.

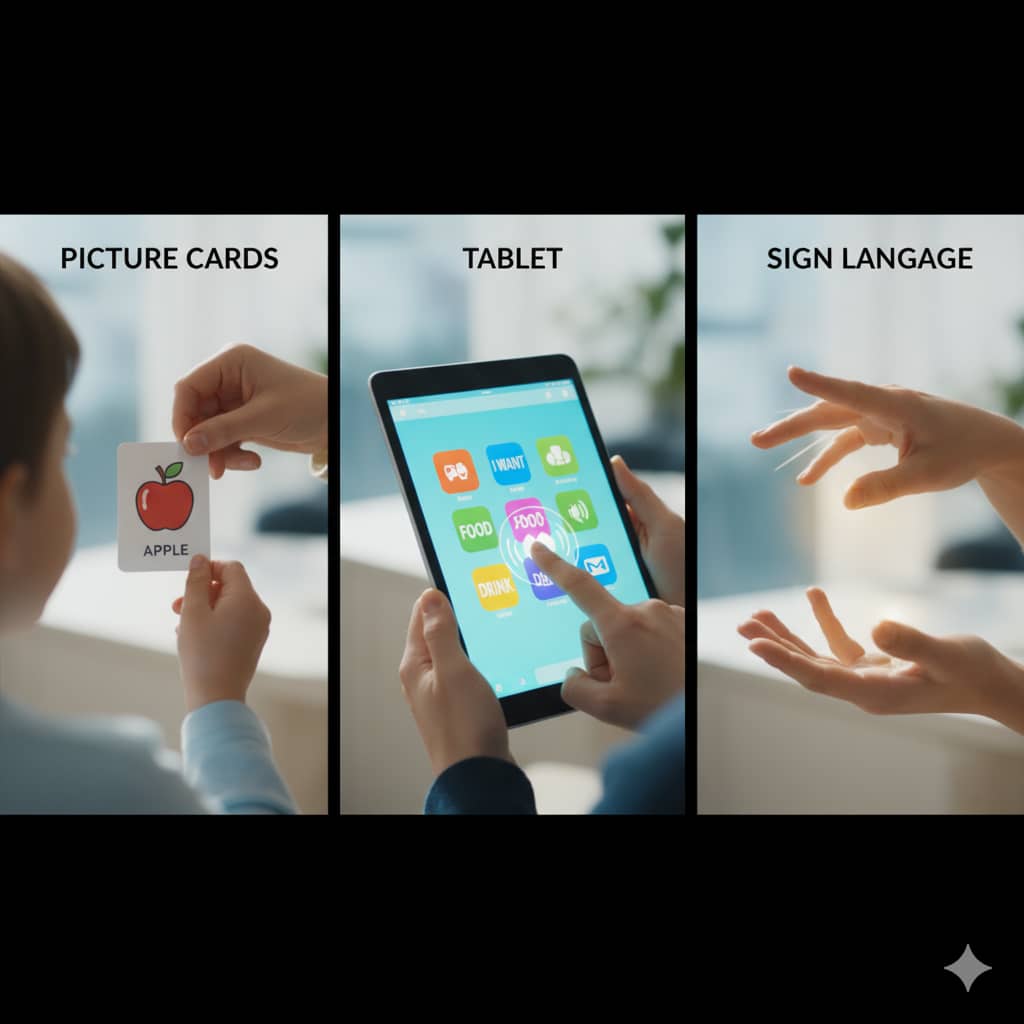

The educational journey requires flexibility and creativity. Individualized Education Programs legally mandate tailored approaches, but the most effective teachers I’ve observed understand that standardization is the enemy of progress. They discover how each student learns best, through visual supports, hands-on experiences, repetition, or technology. I’ve seen non-speaking students compose beautiful sentences using picture boards and teenagers who struggled with traditional math master complex budgeting when taught with real money and practical scenarios.

The transition to adulthood presents particular challenges that extend far beyond academics. Learning to navigate public transportation, manage a budget, understand social boundaries, and maintain employment requires careful teaching and ongoing support. The most successful transitions happen when communities provide gradual, supported experiences rather than sudden immersion. One program I admire partners with local businesses and schools to create graduate work experiences that build skills and confidence over several years.

The role of technology has been transformative. Augmentative communication devices give voice to those who cannot speak. Smartphone apps provide visual schedules and reminders that increase independence. GPS trackers offer safety nets for those who might become disoriented. Yet the most powerful technological tools are often the simplest—I’ve seen a video modeling app teaching social skills more effectively than years of traditional instruction.

The social and emotional lives of individuals with intellectual disabilities are often richer and more complex than commonly assumed. They form deep friendships, experience romantic love, feel pride in accomplishments, and grieve losses. The assumption that their emotional experience is simpler or less nuanced is perhaps the most damaging misconception. I’ve counseled individuals who articulated sophisticated understandings of relationships and their place in the world, once someone bothered to listen in the way they could communicate.

Families navigate a unique journey that changes across the lifespan. Parents of young children often face diagnostic odysseys and service battles, while parents of adults confront the challenge of ensuring lifelong support and belonging. Siblings may take on caregiving roles or advocacy positions they never anticipated. The most resilient families I’ve known are those who learn to celebrate small victories while maintaining realistic expectations, who understand that their loved one’s path will be different, but no less valuable.

Society’s understanding has evolved dramatically, yet stigma persists in subtle forms. Pity, low expectations, and segregation continue to limit opportunities even as inclusion becomes more common. The most progressive communities are those that recognize neurodiversity as a strength, that understand a society including people with intellectual disabilities is more creative, compassionate, and interesting than one without them.

Supporting individuals with intellectual disabilities ultimately comes down to a simple but profound shift: seeing the person first and the disability second. It means presuming competence even when it’s not immediately evident, providing accommodations without making assumptions, and recognizing that every human being has something to contribute. Michael, the grocery bagger, taught me that we all have our own ways of being smart, our own forms of intelligence that may not show up on tests but that make the world better in their own way.

References

Wikipedia contributors. (2002, February 24). Intellectual disability. In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intellectual_disability

Defines intellectual disability as a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by significant impairment in intellectual and adaptive functioning with an IQ below 70, manifesting in deficits in reasoning, problem-solving, and daily living skills before age 18.

Special Olympics. (2023, March 21). What is intellectual disability? Retrieved from https://www.specialolympics.org/about/intellectual-disabilities/what-is-intellectual-disability

Describes intellectual disability as limitations in cognitive functioning and skills affecting conceptual, social, and practical areas, causing slower development and learning differences evident before age 22.

Shree, A., & Shukla, P. C. (2016). Intellectual disability: Definition, classification, causes, and characteristics. *New Delhi Publishers*. Retrieved from https://ndpublisher.in/admin/issues/lcv7n1b.pdf

Presents a comprehensive overview of intellectual disability as significant deficits in intellectual and adaptive behaviors impacting learning, social participation, and practical skills, with intellectual functioning measured by IQ testing.

Cleveland Clinic. (2025, September 10). Intellectual disability: Definition, symptoms, & treatment. Retrieved from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/25015-intellectual-disability-id

Highlights intellectual disability as limitations in intelligence and everyday abilities essential for independent living, emphasizing early diagnosis and tailored support.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). [Referenced in: NCBI Bookshelf, Clinical Characteristics of Intellectual Disabilities]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK332877/