For years, I thought my negative thoughts were just “how I was.” Therapy taught me they were habits, patterns I’d learned and could unlearn. Here’s how I finally broke the cycle.

There was a voice that lived in my head for as long as I can remember. It wasn’t dramatic or cruel in an obvious way. It didn’t scream or threaten. It was quieter than that, more insidious. It whispered. And what it whispered sounded so reasonable, so true, that I never thought to question it.

“You’re not really qualified for this.”

“They probably didn’t mean to invite you.”

“Everyone else seems to know what they’re doing.”

“That thing you said three years ago? They definitely remember it and judge you for it.”

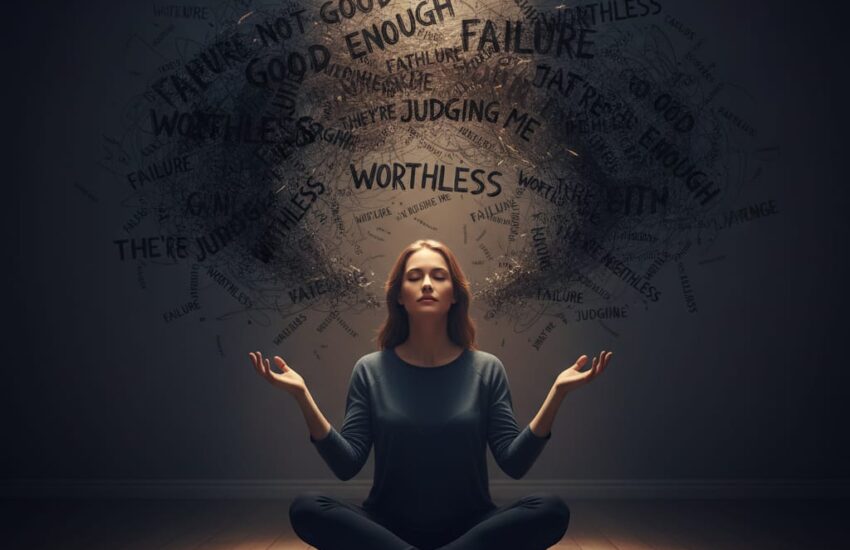

I didn’t know this voice had a name. I thought it was just me, my personality, my realistic outlook, my way of staying humble and prepared. I called it being cautious. Being self-aware. Being honest about my limitations. I had no idea I was living inside a loop of negative thinking that had been running since childhood, quietly shaping every decision, every relationship, every moment of joy I talked myself out of.

The first time my therapist used the phrase “cognitive distortion,” I almost laughed. It sounded like something from a textbook, academic and distant. But then she explained it simply: cognitive distortions are the lies your brain tells you that feel like truth. They’re the filters you see the world through, the grooves your thoughts have worn so deep that you can’t imagine thinking any other way.

And the most disturbing part? I had no idea they were there.

We started with something called “mind reading.” That’s the distortion where you assume you know what other people are thinking, and of course, what they’re thinking about you is negative. I did this constantly. A colleague walks past without saying hello? They’re angry at me. A friend takes hours to respond to a text? They’re upset about something I did. My therapist asked a simple question that stopped me cold: “What evidence do you have that isn’t just a story you’re telling yourself?”

I had none. Not a single fact. Just a lifetime of assumptions dressed up as intuition.

Then came “catastrophizing,” which was my brain’s favorite sport. A small mistake at work wasn’t just a mistake; it was the beginning of a downward spiral that ended with me fired, homeless, and alone. A minor health symptom wasn’t just a cold; it was the first sign of something terminal. My therapist called this “making a mountain out of a molehill,” which I’d heard before, but she added something new: “And then convincing yourself the mountain has always been there.”

She taught me to look for the evidence. To ask myself: What’s actually happening right now, versus what’s happening in the story my brain is telling? The answer was almost always reassuring. Right now, in this moment, I am safe. I am okay. The disaster hasn’t arrived. And it probably won’t.

The hardest distortion to untangle was “labeling.” I didn’t just think I made mistakes; I thought I *was* a mistake. I didn’t just fail at something; I *was* a failure. My therapist pointed out the difference between behavior and identity, between what I did and who I was. “You forgot to respond to an email,” she’d say. “That doesn’t make you a careless person. It makes you a person who forgot to respond to an email.” The distinction felt revolutionary. I had been convicting myself of crimes based on evidence that wouldn’t hold up in any court.

But identifying the distortions was only the beginning. The real work was learning to interrupt them.

My therapist introduced me to something called “cognitive restructuring,” which sounds complicated but is really just learning to talk back to your own thoughts. When the voice whispered, “You’re going to embarrass yourself at that meeting,” I learned to ask: “Is that a fact or a fear?” When it insisted, “Nobody really likes you,” I learned to list the evidence against it, the friend who called yesterday, the colleague who asked for my opinion, the partner who said I love you this morning.

At first, this felt fake. Performative. I didn’t believe the counter-arguments any more than I believed the negative thoughts. But my therapist assured me that belief follows practice. You don’t wait until you feel confident to challenge the thoughts; you challenge the thoughts until you feel confident. It’s repetition that rewires the brain, not inspiration.

She was right. Slowly, over months, the voice got quieter. Not silent, never completely silent but less commanding. Less convincing. I started to notice the space between a thought and my belief in it. That space, my therapist said, is where freedom lives. Between stimulus and response, between the whisper and the acceptance, there’s a gap. And in that gap, you get to choose.

I also learned where the voice came from. We traced it back, gently, to childhood messages I’d absorbed without realizing it. A teacher who praised only perfection. A parent who meant well but compared me to others. A culture that rewarded achievement and treated rest as laziness. The voice wasn’t mine, not really. It was a compilation of every critical voice I’d ever encountered, internalized and looped until it sounded like my own.

This realization was both painful and liberating. Painful because I had to feel old wounds I’d long ignored. Liberating because if the voice wasn’t mine, I could unlearn it. I could choose new messages. I could become the one who speaks to myself with kindness instead of criticism.

One of the most practical tools my therapist gave me was the “thought record.” Every time I noticed a negative thought spiraling, I would write it down. Then I’d write the distortion it represented. Then I’d write a more balanced thought, not blindly positive, just realistic. For example:

Negative thought: “I ruined that conversation by saying something stupid.”

Distortion: Mind reading and labeling.

Balanced thought: “I said one thing that might have been awkward, but the conversation continued normally and no one reacted negatively. I’m judging myself more harshly than anyone else is.”

It felt mechanical at first, like homework I didn’t want to do. But over time, it became automatic. I started catching the distortions in real time, before they could take root. I started offering myself the same compassion I would offer a friend. I started to realize that the voice in my head wasn’t truth, it was just a habit. And habits can be broken.

The change didn’t happen overnight. It happened in increments so small I almost missed them. A day when I didn’t replay an awkward moment for hours. A conversation I didn’t overanalyze afterward. A compliment I accepted without deflecting. A mistake I forgave myself for within minutes instead of weeks.

I still have negative thoughts. Everyone does. But now I see them for what they are: passing mental events, not permanent truths. They’re like clouds moving across the sky, and I’m the sky, unchanged, unbroken, still here when they pass. Therapy didn’t stop the clouds from coming. It just helped me remember that I’m not the clouds. I’m the vast, open space they move through.

If you’re trapped in a cycle of negative thinking, if the voice in your head is cruel and constant, if you’ve started to believe the lies it tells, please know this: it doesn’t have to be this way. You don’t have to live inside that loop forever. There are tools, and there are people trained to help you use them.

Therapy isn’t about becoming a different person. It’s about becoming more fully yourself, the self that existed before the voice took over, the self that knows its own worth, the self that can look at a negative thought and say, gently, “That’s just a story. And I don’t have to believe it anymore.”

I believed mine for decades. Now I question everything. And in that questioning, I’ve found something I never expected: peace.

References

Topper, M., et al. (2018). *The effects of cognitive-behavior therapy for depression on repetitive negative thinking: A meta-analysis*. *Behaviour Research and Therapy, 106*, 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.04.002

Luyten, P., et al. (2025). *Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy in treating repetitive negative thinking: A transdiagnostic meta-analysis*. *Psychological Medicine*. Advance online publication. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39916353/

City Behavioral Health. (2025, October 22). *Using CBT techniques to overcome negative thought patterns*. Retrieved from https://citybehavioralhealth.com/using-cbt-techniques-to-overcome-negative-thought-patterns/

Simply Psychology. (2025, July 6). *13 cognitive distortions identified in CBT*. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/cognitive-distortions-in-cbt.html

Positive Psychology. (2026, January 9). *Cognitive distortions: 15 examples & worksheets (PDF)*. Retrieved from https://positivepsychology.com/cognitive-distortions